Thank you for that kind introduction. It’s a great honour to be here.

I should start by declaring that I am no educationalist. I don’t work in education and I’m not an academic. Nor am I a policy wonk. The best I can claim is a degree in English Literature from a chilly university in the Fens, and I’m not sure that counts.

What I do have, though, which is the main reason I’m here, is lived experience of parenting a very different kind of child, a very different kind of young person.

For my second son, Joey, now 27, has intractable epilepsy and profound learning disabilities. There are going to be some pictures of him projected behind me for when I get boring.

He has a big smile and an infectious laugh but needs help with the most basic life skills. He can say ‘no’, ‘yes’ and, delightfully, ‘cup of tea’, and communicates with a mixture of basic Makaton signing, PECS (the Picture Exchange System) and dogged persistence. He’s much loved and generates great joy, but there is no denying the severity of his disabilities.

But being Joey’s dad has changed my life. It has also helped me rethink the values that I was brought up to cherish.

I’ve just finished writing a book which charts how changing attitudes to learning disabilities have led to changed lives, both for good and ill. It has shown me that we cannot educate and support learning-disabled people effectively without some understanding of the history and culture that surrounds them.

And that is the issue I want to explore this afternoon, along with some general thoughts about the education of people like my Joey.

1.

But what do we mean by learning disabilities?

There is widespread agreement about three characteristics:

First, learning-disabled people have relatively limited intellectual capacities and need support to live safe, happy and healthy lives.

Second, most learning disabled-people were born with their impairments, which are not curable through medical intervention.

Third, although learning disabilities are sometimes associated with physical disabilities, these are distinct phenomena.

Learning disabilities are, of course, not the same as learning difficulties. While challenges such as dyslexia, dyspraxia and dyscalculia can be managed, even overcome, a learning disability is permanent. The two sometimes overlap, but the word ‘difficulty’ is too often a euphemism for what is, by any standards, a genuine impairment.

The causes are many. Everyone who has Down’s Syndrome has a learning disability, as do some people with cerebral palsy, spina bifida and other physical impairments. There are several genetic syndromes which affect cognitive abilities, and some autistic people are also learning disabled, though by no means all.

For the majority, however, (including my Joey) the cause is unknown.

Contradictions are rife: thus, some learning-disabled people are non-verbal, others chatter away happily; some have problems with physical co-ordination, others are remarkably dextrous; some enjoy human contact, others are introverted; some have an innate musicality, while others are distressed by audible stimuli. The crucial point is that, like all human beings, everyone with a learning disability is different, and generalisations are best avoided. As is sometimes said: ‘When you’ve met one learning-disabled person, well, you’ve met one learning-disabled person.’

There are as many as one and a half million such people in Britain today (about 2% of the population) and they’re to be found in every class, ethnicity and demographic.

This is, by any standard, a large and loosely defined population.

2.

Curiously, attempts at labelling and diagnosis such people haven’t always helped.

It was in the late eighteenth century that so-called ‘idiots’ started to be seen as an identifiable group, requiring specialist education, support and care, while prompting questions about the nature of their condition and, astonishingly, to what extent they could be accepted into the category of the human.

The mid nineteenth century saw the opening of specialist asylums, although most learning-disabled people stayed with their families, surviving as best they could. Optimism was in the air and, oddly, some people thrived.

By the late 1800s, however, and influenced by the pseudo-science of eugenics, ‘the feeble minded’, as they were often called, were increasingly seen as an existential threat, ‘a social menace’ to be institutionalised en masse.

New categories were created, with terms like ‘imbecile’, ‘moron’ and ‘mental defective’ indicating varying degrees of impairment. These dictated accommodation in asylums and institutions, with the most severely disabled hidden as far away as possible.

But the strange fact is that many of these people weren’t learning disabled at all. They were alcoholics, unmarried mothers, dyslexics, schizophrenics—a range of misfits that polite society preferred to avoid.

Nevertheless, and responding to an entirely unproven fear of heritability, tens of thousands of people across America and continental Europe were forcibly sterilised, leading, ultimately, to the horrors of the Nazi persecution, which resulted in the systematic murder of as many as 250,000 disabled people. They were, apparently, leading ‘lives unworthy of life’.

After the war, more labels appeared with ‘subnormal’, ‘retarded’ and ‘mentally handicapped’ suggesting a range of deviation from the so-called ‘norm’, and support dictated—and rationed—by such tags.

And, of course, the process continues.

Now, I recognise that a diagnosis can be helpful, and I’m certainly not anti-science. But I often find myself quietly content that the cause of Joey’s disability remains a mystery. What matters is ensuring that he has an appropriate education and a good life, not what words are used to describe his impairments. A label doesn’t always guarantee a better life. At times, it’s done the opposite. ‘Label jars, not people’, as activists sometimes say.

It's just the first of several contradictions.

3.

A second can be found in the way that artists and intellectuals—often self-proclaimed progressives, perhaps like some of us here—embraced the very worst aspects of eugenics.

And it’s pretty grim stuff, I’m afraid.

Thus, Bernard Shaw enthused that ‘eugenic politics would finally land us in an extensive use of the lethal chamber’, where ‘a great many people would have to be put out of existence simply because it wastes other people’s time to look after them’.

Using the same ghastly phrase, DH Lawrence dreamt of ‘a lethal chamber as big as the Crystal Palace, with a military band playing softly’. He volunteered to ‘bring them all in, the sick, the halt and the maimed’, boasting that he ‘would lead them gently, and they would smile me a weary thanks; and the brass band would softly bubble out the Hallelujah Chorus.’

Worst of all is Virginia Woolf’s diary entry for 9th January 1915, where she describes meeting ‘a long line of imbeciles’:

‘The first was a very tall man, just queer enough to look at twice, but no more; the second shuffled, & looked aside; and then one realised that everyone in that long line was a miserable ineffective shuffling idiotic creature with no forehead, or no chin, & an imbecile grin, or a wild suspicious stare. It was perfectly horrible. They should certainly be killed.’

No ‘room of their own’ for learning-disabled people, it seems.

Astonishingly, the defeat of Nazi Germany didn’t bring an end to such thinking.

Indeed, William Beveridge, the beloved creator of the Welfare State, slipped out of the gallery of the Commons during the debate about his report to reassure the Eugenics Society that his plan was, quote, ‘eugenicist in intent and would prove so in effect.’

Meanwhile, the psychiatrist Dr Alfred Tredgold updated his influential Textbook of Mental Deficiency to recommend euthanasia for the ‘80,000 or so idiots and imbeciles’: ‘Many of them are utterly helpless, repulsive in appearance and revolting in their manners. Their existence is a perpetual source of sorrow and unhappiness to their parents. In my opinion it would be an economical and humane procedure were their very existence to be painlessly terminated.’

Such prejudice from the learned hasn’t ended, with the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins arguing that eugenics would work if only we didn’t have ‘moral qualms’, and the much-lauded philosopher Peter Singer insisting that people like my Joey have no greater ‘moral value’ than intelligent animals.

It’s clear that a good education is no guarantor of decency.

4.

Tragically, something of this contempt was hard-wired in the 1946 National Health Service Act, which took more than 100 ‘mental defect’ asylums into public ownership and turned them into long-stay hospitals.

By 1957, 125,000 people lived in such places, deprived of dignity, freedom and basic human rights. These hospitals were soon starved of funds, resulting in an epidemic of neglect, abuse and cruelty.

The 1960s and 70s saw high-profile inquiries into some of these institutions and slowly, much too slowly, they were closed and the people who’d been incarcerated in them were moved out. All too often, however, they were torn from places they’d lived in for decades and abandoned with little help or support. Indeed, learning-disabled people living lonely lives ‘in the community’ seem particularly vulnerable to fraud, exploitation and violence.

It’s not as if the curse of bad institutions was lifted. Although many of the large ones were closed, smaller ones survived, some even thrived, and we now find ourselves in the grotesque situation of various private companies making vast profits running care homes which are not fit for purpose.

And then, of course, there are the Assessment and Treatment Units where some of the worst violations have taken place, often defended as a response to so-called ‘challenging behaviour’. There are more than 2500 people locked up in these dreadful places today.

It’s tempting to dream of steady improvement. The depressing fact is that progress has been glacial: two steps forward and one step back is common, but so often, tragically, is one forward and two back.

The Whig version of history hardly applies to learning-disabled people.

5.

The last half century has seen some big shifts in thinking. What’s striking, again, is how contradictory these are.

Thus, the theory of ‘normalization’, the idea that learning-disabled people should be able to live ‘normal lives’, depends on an agreement about what is meant by ‘normal’. Not easy to define, as I’m sure you’ll agree.

Then, there’s the ‘social model’. This insists that people are disabled by society, not their impairment, and that instead of dwelling on deficit, we should accommodate difference. The problem is that this is much easier to redress with physical disabilities than intellectual ones: it’s one thing to make buses physically accessible, quite another to insist that bus drivers learn Makaton.

It's also triggered a debate about whether we should regard learning disabilities as an impairment at all, with some insisting that we should be talking about ‘learning differences’ and, increasingly common, ‘neurodiversity’.

I have a problem with this. Which is not to say that Joey is only disabled. But there are many things he can’t do that almost every human being his age can do, and hardly anything that he can do which others cannot. As such, he is distinctly disabled, and it is dishonest to say anything else.

Finally, self-advocacy insists that the best way to secure flourishing lives is to let learning-disabled people speak for themselves and listen to what they have to say. It’s a tremendous ideal, but hard when it comes to people with severe learning disabilities. Self-advocacy, by its very nature, privileges the most articulate.

As a result, I think we should ask what we mean by self-advocacy. For Joey’s presence at a meeting about his future is a speech act in itself and should be understood as such. His beating heart and living breath make him much more than a name on a sheet of paper.

The essential point is that we should engage with the realities of the individual’s needs instead of imposing crude templates on such a diverse and loosely defined group.

6.

Before I turn my attention to education, I’d like to lighten the mood by sharing something positive.

It was the afternoon of New Year’s Day 2021, and I was lying on the sofa with Joey, giggling at one of our jokes. I took a few selfies and tweeted one of them out with the simple, ironic message: ‘So terrible being the dad of a learning-disabled young man.’ I thought nothing more of it until I went back to my phone and saw a steady stream of learning-disabled children, young people and their families doing happy, ordinary things.

Each carried its own message of mock gloom to which I replied with mock sympathy. For three frantic hours, I could hardly keep up, and when I woke up on Saturday it was still going strong. By Monday morning I was on Radio 4 talking about what it meant.

Something similar happened on the day children get their GCSE results: I tweeted a picture of Joey with a request to ‘remember the young people who’ve never got a qualification in their lives’. The biggest, however, was on Joey’s 25th birthday, when I posted a picture with the simple message that, ‘He’s never said a word in his life, but has taught me so much more than I’ve ever taught him.’ It received a huge response (80,000 likes) and was, for a moment, ‘trending’.

The crucial point is that people were opening their hearts and minds to learning-disabled people and recognising their value.

But while I love such positivity, I think we should be careful.

The first reason is because parents and siblings shouldn’t be bullied into stifling negative emotions. Joey’s family often find him maddening. Forgiving ourselves is essential not just for us, but him too.

The bigger danger is that such boosterism creates hierarchies.

Thus, a leading charity has recently rolled out an awareness campaign called ‘MythBusters’. This aims to discredit the idea that learning-disabled people are incapable, and profiles people who are achieving great things. This, it is argued, will help the public think of such people in a more positive way.

The danger is that it creates a hierarchy within learning disabilities, with the high achievers at the top and people like Joey at the bottom. It unwittingly suggests that people only deserve support if they’re capable of achieving great things. And, of course, that if they achieve great things they don’t need support.

The law of unforeseen consequences, I suppose.

7.

And so to education.

The history of special education is, well, educational.

The story starts one day in 1798 when an eleven-year-old boy was found living in the woods of Southern France, nonverbal and with no understanding of society. He was taken to Paris where he struck a chord in a post-revolutionary society eager to define the essential qualities of the human, while indulging the romantic image of a life free of the artifice of civilisation.

The idealistic young doctor Jean-Marc Itard offered to teach the ‘wild boy’.

Itard’s stated objective was educational, but so also was it philosophical. He saw Victor, as he soon named him, as someone who’d not been tainted by civilization and could, with proper teaching, become a ‘full human being’. Whereas others had dismissed him as ‘an incurable idiot, inferior to domestic animals’, Itard insisted that he could be helped. And under his tuition Victor made some progress, even learning some simple communication. His great breakthrough, apparently, was saying ‘lait’ (milk). A bit like Joey’s ‘cup of tea’. The two go together.

What’s distressing, however, is the cruelty of some of Itard’s methods: Firing pistols near Victor’s ear, exposing him naked to the cold, repeatedly giving him electric shocks and, at one point, hanging him head-first out of a fourth-story window.

And the advances were minimal and, after five years, Itard was in despair: ‘Since my pains are lost and my efforts fruitless, take yourself back to your forests and primitive tastes.’

Itard was especially mortified to discover that Victor’s childhood had failed to protect him from the usual adolescent vices. He was soon moved out of the Institute and lived with Itard’s housekeeper who cared for him until his death nearly twenty years later.

This episode presents us with a paradox. On the one hand, Itard’s extensive investigations suggested that learning-disabled people were capable of development, thus encouraging the special educationalists who followed; on the other, his elevation of intellectual capacity as fundamental to human status contributed to the growing sense of the ‘idiot’ as being beyond the pale.

As one historian bluntly put it, Victor’s ‘inability to acquire language—as evidence of reason and human status—sealed his abandonment’.

It’s a salutary lesson to us all.

8.

The late nineteenth century brought growing optimism about the educability of learning-disabled people, and the 1890s saw the opening of scores of ‘silly schools’, as they were called, along with a proliferation of theories about how best to teach such people, often with some success.

However, with the turn of the century and—ironically—the introduction of IQ tests, people with learning disabilities were increasingly thought to be ineducable, and the important thing was to prevent such people reproducing.

The carefully segregated institutions usually paid lip service to an educational purpose but, with the new pessimism, education was seen as largely pointless.

Indeed, the 1944 Education Act divided children into the ‘educable’ and the ‘ineducable’, with schooling only compulsory for the first category.

By the early 1960s, about 40,000 children were being taught in schools for the ‘educationally subnormal’, a phrase still heard in the 1980s.

In 1967, Stanley Segal’s polemic, No Child is Ineducable, made the case for universal education in the strongest terms, paving the way for the 1970 Education (Handicapped Children) Act, which transferred responsibility for learning-disabled people from the NHS to local education authorities.

It is telling, however, that Segal felt compelled to produce a follow-up book in the 1980s which challenged educators to deliver what had been promised, and a report from 2009 declared that the education system is still ‘living with a legacy of a time when children with Special Educational Needs were seen as ineducable’.

So long as this idea endures, so long as some children are deemed beyond the pale, we’re letting them down in the worst way imaginable.

The 1970 Act didn’t resolve how such education should be delivered and soon Margaret Thatcher, then education secretary, asked Mary Warnock to chair an enquiry. The chief recommendation of her wide-ranging report was to replace individual educational ‘handicaps’ with the catch-all category of ‘special educational needs’. This formed the basis of the 1981 Education Act, which insisted on mainstream settings wherever possible, gave parents new rights, and introduced ‘statements of special educational needs’.

The goal of ‘inclusion’ was central to New Labour’s vision and the 2001 Special Educational Needs and Disability Act stipulated that disabled children should, wherever possible, have the same experiences as their non-disabled siblings, with adaptations being made to ensure that they could participate in mainstream schooling. Above all, the Act outlawed discrimination and launched the system of SEND Tribunals.

This moment of optimism was not to last, however, and, in 2005, Warnock admitted that the system she helped create was ‘needlessly bureaucratic,’ describing inclusion as the ‘disastrous legacy of her report’. She even wrote a pamphlet promoting special schools. David Cameron’s Conservatives announced that they wanted to ‘end the bias towards the inclusion of children with special needs in mainstream schools’, reflecting a concern that inclusion had ‘gone too far’ and responding to the view that learning-disabled pupils were holding back their more able peers.

The swings in government policy are dizzying and those of us with lived experience of learning-disabled children have learnt to be cautious of all such announcements. Too often they feel simply performative. Our children deserve better.

9.

Before we turn to the current situation, we should take a moment to consider the nature of educating people with severe learning disabilities.

As we’ve seen, each person is different, but what I’ve observed with Joey is a continuous series of tiny markers of progress. He’s never going to get a place at Balliol, but he learns all the time, and to teach him properly you need to take pride in small steps: putting his trousers on the right way round, organising PECS to plan his day, using a bank card at the shops, emptying the dishwasher, laying the table. But you also have to develop routines, recognisable events that he can engage with, jokes that make him laugh. Creativity is essential. But then, creativity is always essential, not just with Joey.

Joey is no longer in formal education, and he lives in supported living, but his education continues, his development continues, he keeps on learning. And the key to that is interaction with people who have the right attitude, the right confidence, the right commitment, above all the right culture.

It’s sometimes said that ‘culture eats strategy for breakfast’ and nowhere is this truer than in special education: you can have all the best equipment, technical skill, smart buildings and glossy brochures, but without that ‘can do’ approach, that spirt of optimism and engagement, children with learning disabilities will always be let down.

Culture matters and it is culture, above all, which is behind everything that follows.

10.

You will all know about the current provision, a mixture of mainstream for those with moderate disabilities, and special schools for those with more pronounced challenges. There are strengths and weaknesses with both, and you’ll have your own opinions.

But what is the experience like for learning-disabled children, young people and their families?

In the spirit of inquiry, I posted a Tweet last month asking exactly that. I got hundreds of replies. And various themes emerged.

The chief concern about the mainstream was that the child’s individual needs were in danger of being overlooked in an increasingly competitive culture of exams and high achievement.

It was repeatedly said that a placement depended, above all, on the right culture. The problem is that this is usually delegated to the SENCOs, sometimes a junior teacher with limited sway. And, while teacher training includes special education, there is no requirement, apparently, for SENCOs to have ever worked with disabled children. Mainstream schools need to have trained staff in this field if they are to deliver.

But special schools have problems too.

There are evidently some excellent ones, but the concern is that they are in danger of becoming dumping grounds for a wide range of disabled children with little sense of why they’re being educated together.

What’s more families often have little connection to the broader community. Pupils frequently have to travel long distances and transport is required (and increasingly denied, especially to over 16s, even in this great city of Birmingham). Communication depends on ‘home-school books’ and can be patchy and it’s hard for families—often isolated already—to feel connected to the school and other families.

The common theme in both settings was a lack of individualisation. Even those with the best experiences—and there were many—felt that their child’s specific needs weren’t being taken seriously. We obviously have some way to go before we deliver a fully ‘person-centred’ approach when it comes to ‘different’ children.

Meanwhile, parents, who are often dealing with a host of other challenges—from family stigma to marital breakup, failure to hold down a job to fighting for appropriate medical care and equipment—are forced into a never-ending battle to secure for their child the education he or she so obviously needs and deserves.

Navigating the system is agonising, and families are often driven to despair. There are many good things about the 2014 Children and Families Act’s attempt to deliver a joined-up approach, but the local authorities have often found it hard to deliver on the Education and Health Care Plans.

Parents are plagued by these plans, staying up all night worrying whether the mandatory Section F will secure the support that their child requires. Imagine parents of non-disabled children fretting about such basic things.

The dismal fact is that hard-pressed local authorities increasingly try to duck their statutory duties and, while most families who go to tribunal are successful, some councils spend vast sums of money on legal services of their own, with a recent report putting this at £60 million a year. What a staggering waste of money. I should have been a lawyer.

In many ways, Joey has been lucky. But we, too, found ourselves involved in endless letters, phone calls and meetings with lawyers, and I sometimes try to imagine what it would have been like if we spoke no English or were overawed by the authorities, let alone lived the chaotic lives that are so common. The process is needlessly bureaucratic and riddled with bear traps, and I have boxes full of letters and reports. Indeed, I once calculated that, for five critical years, we averaged eight hours a week fighting for Joey’s educational future.

At its worst it feels as if the local authorities think that some children are indeed ineducable, or at least that their education is a waste of public money.

And it takes it out of us to resist this disastrous logic.

11.

The truth is that the battles never stop.

Thus, while our non-disabled kids spend the summer going to holiday clubs or hanging out with their friends, their disabled brothers and sisters have little access to such support, and parents are exhausted before the school reopens.

And when term finally starts, they have a huge list of things to worry about: Will the transport arrive? Will the chaperone have had epilepsy training? Will the speech and language therapy be in place? Will the occupational therapist turn up? Will the therapy pool be working? And so much more.

The blunt truth is that the system must be made more effective and proactive, less appallingly stressful, if it is to stand a chance of delivering on its extravagant promises.

I’m afraid the schools themselves don’t always help. At worst, parents are made to feel guilty for imposing on them the burden of educating their child. I was appalled to read the Times Educational Supplement a couple of years ago offering SENCOs advice for dealing with ‘challenging parents.’ The writer described three kinds of parents (‘angry’, ‘pandering’ and ‘non-engaging’) and gave patronising advice on how to engage with each.

As I wrote in reply, ‘All parents of disabled children are different. What unites us is the experience of having to fight and fight again for their basic human rights. We’ve only become tigers because we’ve had to and would do anything to lay our burden down.’

SEN funding is frankly inadequate. In 2019 the Education Select Committee forcefully criticised existing provision with one MP calling for ‘a transformation, a more strategic oversight and fundamental change to ensure a generation of children is no longer let down’. But this is impossible with the endless circulation of ministers and political initiatives which are, I’m afraid, more often performative than effective, offering photo ops but little more. And with massive pressures on local authority budgets, it is hard to know how or when these issues will be resolved.

But if we don’t resolve it, if we just let things drift, if we ignore these problems, we don’t deserve to call ourselves a civilised country. Certainly, the damning report by the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Disabled People should shame us all.

12.

So, what can we do?

‘Diagnostic overshadowing’ is a useful term in health care. It means that the clinician is so mesmerised by the disability that he or she fails to notice the actual issue. I think something of the same applies in education.

The fact is we have got a long way to go before we treat learning-disabled children and young people as individuals, with their own strengths, their own challenges, their own needs.

Two things are required.

First: Listen to the families. We are the people who know the young person best. But all too often we find ourselves side-lined, sometimes by people who don’t know our children, and who may be less informed about the realities of learning disabilities than we are.

Second: Listen to our children. Some learning-disabled people are very articulate, others less so, but educators need to develop a way of listening to them, looking at them, engaging with them, above all respecting them, and discovering what it is they need to flourish. It’s an art as much as a science but it is essential.

And it is here, I think, that we need to rethink the concept of ‘inclusion’.

We tend to think that ‘inclusion’ simply means sending disabled children to mainstream schools and that retaining special schools is the opposite of ‘inclusion’. While I think including disabled children in the mainstream is often an excellent idea and that there are many ways of making it work better, real inclusion means something much deeper.

It means insisting that learning-disabled children have the same rights as any other child.

It means recognising that there is no substantial difference between learning-disabled and non-disabled children, even if some of their day-to-day needs are different.

If inclusion means anything it’s that all our children matter, and little gives a better indication of a society’s health than our ability to be true to that simple mantra.

The theme of this conference is ‘belonging’. But are we sure that all of our children belong? It sometimes feels that children with learning disabilities don’t.

13.

And with that in mind, I’d like to conclude by suggesting three key principles that we should adopt in thinking about learning-disabled people, in schools, colleges and the world at large.

First, it’s time to be realistic. While I understand the wish to be positive, to emphasize the remarkable things that some learning-disabled people can do, if we deny the realities of intellectual impairment—Joey’s lack of speech, his limited comprehension, his lack of physical coordination, and so on—we will further exclude and devalue people like him with the most acute needs. This shouldn’t be an excuse for pessimism or hierarchy. But if we don’t deal with the realities, we will continue to let such people down. It’s time to get real.

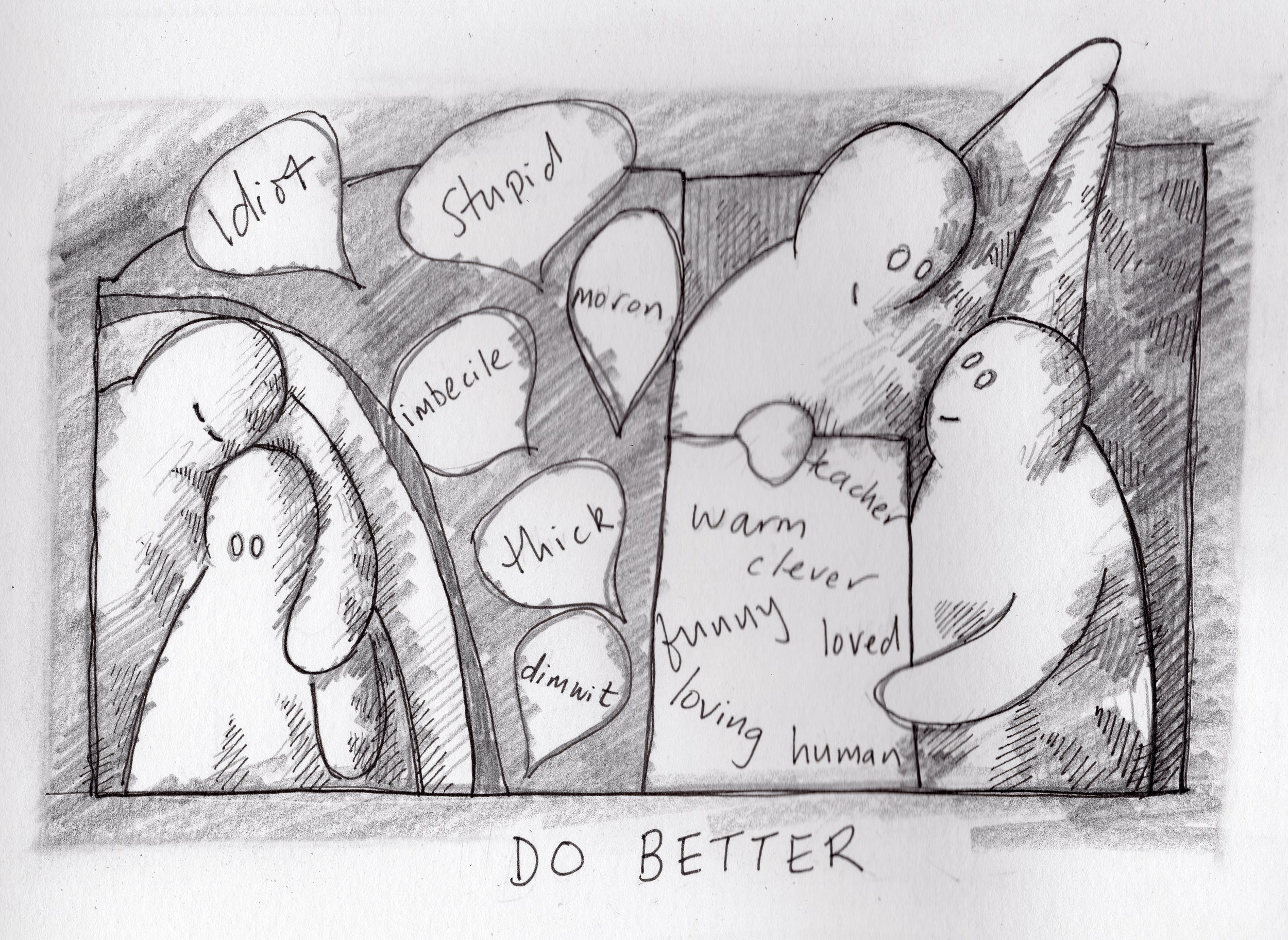

Second, we need to rethink our hierarchy of values. In a world without God and little faith in politics, along with the erosion of shared social responsibility and the championing of the individual, we value intellectual ability above everything: above community, above care, above friendship, above love, even. And this, Joey has shown me, is a terrible mistake. Because while I value the life of the mind enormously—I really do, I absurdly do—it’s clever people like us who do harm, not learning-disabled ones. Certainly, Joey has taught me that there are many worse things in the world than being learning disabled and I wish those dreadful words—‘idiot’, ‘moron’, ‘retard’ and all the rest—were no longer acceptable as insults and disappeared in that place where other historic terms of abuse are thankfully buried. ‘There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy’, says Hamlet, and I wish we remembered that more often.

Finally, we should get serious about human rights. Every child, every person, however disabled, however different, however particular, has a right to a decent, safe and healthy life—including an education—and we must stop trying to evade that responsibility. Surely, a society as rich, as successful, as powerful as ours can ensure that it grants its weakest members the same rights as it grants the strongest. Why was it such a fight to ensure that Joey had a decent education, but by comparison so straightforward for his non-disabled sister and brother to have one? Why does the system throw so many roadblocks in the way? Why do we treat learning-disabled people so differently from the rest? When are we going to right this wrong?

And that is the question that our society has still not adequately answered. But while it remains unanswered, our loved ones, our beautiful children and young people, will linger outside in the cold: ignored, neglected and forgotten.

And this is what I hope you will embrace in your schools and your classrooms, your governors’ meetings and your staff rooms. But, also, in your homes, with your families and in the world at large.

Learning-disabled people have as great a claim to human value as any of us. The sad fact is we have let them down for far too long, and things need to change.

Ladies and gentlemen, it’s in your hands.

So terrible being the dad of a learning disabled young man. pic.twitter.com/innKcdKFje

— Stephen Unwin (@RoseUnwin) January 1, 2021 " target="_blank" class="sqs-svg-icon--wrapper twitter-unauth">