What do we think about the way otherwise impeccably liberal organisations resort to the word ‘idiot’ so often?

The recent announcements that the Birmingham Rep is presenting a show using Spitting Image puppets called Idiots Assemble, that Nottingham Playhouse and Stratford East are staging a new play entitled Village Idiot, and that The New European is publishing a ‘bookazine’ entitled Bloody Idiots are just the latest examples. Two plays at the National Theatre used the same term unchallenged recently (and one, which elsewhere championed the rights and dignities of physically disabled people, happily called people ‘morons’) and it pops up wherever you look.

We believe that this tendency should be challenged.

Why do we care? Well, above all, because we’re both parents of young lads with learning disabilities: Joey (26) has no speech, epilepsy and severe cognitive impairments, and Harry (15) has Down’s syndrome and less profound but significant issues. For centuries they would have been labelled ‘idiots’ (Harry might have been called a ‘Mongolian imbecile’) and both would have suffered dreadful discrimination as a result.

We recognise that very few people would call our lads ‘idiots’ today (although ‘retarded’ and ‘handicapped’ and worse are still heard) and we’re not saying that everyone who uses the word is a bigot, certainly not the editor of The New European or the Artistic Director of the Birmingham Rep. What we do feel is that the word serves no real purpose, reflects unconscious bias and has outlasted its usefulness.

The word itself has a curious history. Taken from the Greek word for a private person who played no role in public affairs, it increasingly conflated a lack of education with intellectual impairment. Thus, when Macbeth describes life as ‘a tale told by an idiot’ he means a story spoken by someone with no social status whose intellectual powers may be limited as a result. Indeed one scholar has argued that everyone outside the tiny number of educated gentry and nobility would have been considered an ‘idiot’.

It was in jurisprudence that the word first developed its modern meaning with courts establishing whether an heir had the intellectual capacity to manage his estate (the management and proceeds of an ‘idiot’s’ estate would revert to the Crown for his lifetime, much to the Crown’s profit). Wordsworth’s Idiot Boy (1798) reflected Romanticism’s interest in the innocence of the intellectually disabled, but it was the massive programme of institutionalisation in the mid nineteenth century that really cemented the word’s modern meaning.

Thus, the Royal Earlswood National Asylum for Idiots opened in the 1850s and others with similar names quickly followed. Then in the 1880s John Langdon Down came up with his Ethnic Classification of Idiots, and the Idiots Act of 1886 shifted responsibility for ‘idiots’ away from the family and onto the state. An ‘idiot’, then, was a person who could not live independently because of his or her cognitive disabilities and, consequently, was best confined to an asylum of one kind or another.

By the turn of the century, with the dominance of eugenics in the social sciences, ‘idiots’ were regarded as the lowest category of the intellectually disabled (see the ‘Steps in Mental Development’ from Virginia in 1915 above) and supposedly posed a ‘social menace’. Soon a toxic collection of scientists, intellectuals, journalists, feminists and politicians set out to stop them from reproducing, and ‘idiots’ were increasingly deprived of their basic human rights, packed off to live in ‘special hospitals’ or ’colonies’, sterilised across Scandinavia and the United States, and murdered in their tens of thousands in Nazi Germany.

1945 did not bring an end to such discrimination, however, and until the 1980s people like our lads endured dreadful neglect and abuse in specialist institutions. And still they face endless challenges: their life expectancy is limited by a health service that too often fails to engage with them, many are confined to Assessment and Treatment Units and cannot come home, and even the most fortunate need their parents to fight continuous battles to secure for them their most basic human rights.

‘Steps in Mental Development’, in Mental Defectives in Virginia. A Special Report of the State Board of Corrections, 1915.

And this is the essential background to why we don’t like the word ‘idiot’.

We have found that people are surprisingly touchy—angry even—when we object to its use, with even the most liberal minded complaining that we’re trying to censor them or that this is ‘political correctness gone mad.’ But people who rightly object to the use of similar language from the dreadful history of racism, sexism and homophobia seem oblivious to the similarly dreadful history of learning disabilities.

One of the most common arguments is that today the word simply refers to people who do ‘idiotic’ things and are not up to the job: language evolves, we’re told, and we’re being picky, over sensitive even. But the awkward fact is that the meaning of the word hasn’t fundamentally changed, for our lads, too, can’t hold down much in the way of jobs and they too sometimes do ‘idiotic’ things. And so, if, as is sometimes claimed, ‘idiot’ doesn’t mean limited intellectual ability, what on earth does it mean?

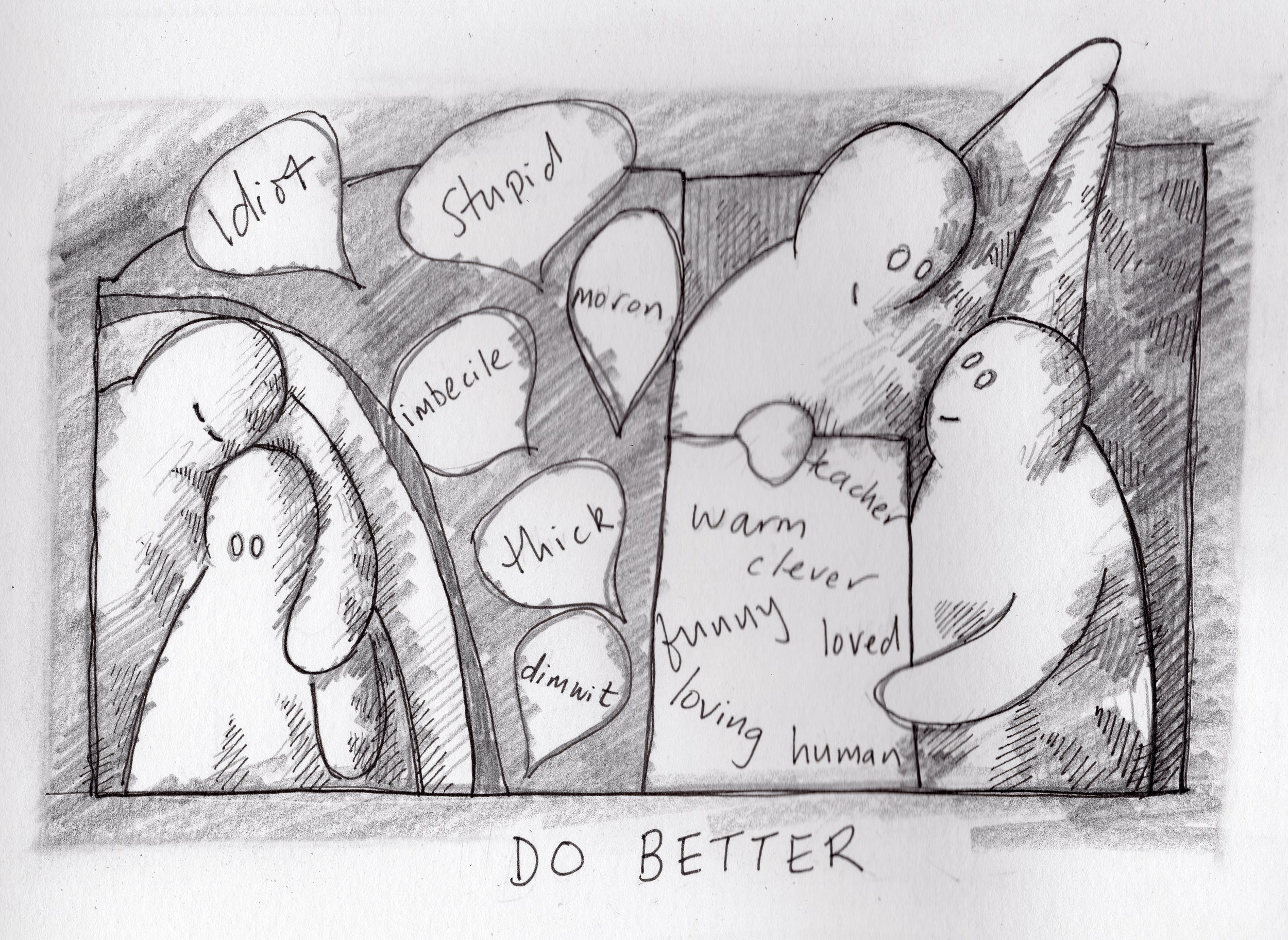

This, of course, reflect a deeper question. Unsurprisingly perhaps, progressive intellectuals hail intelligence as the most important quality a person can have—‘The unexamined life is not worth living’, according to Plato’s Socrates—and tend to despise its opposite, or at least relish such stupidity as an expression of naked humanity. But it’s the underlying note of mockery that really hurts. It’s almost as if the worst thing anyone can be is an ‘idiot’, whereas we know that the vast majority of people with intellectual impairments are kind, warm-hearted, decent people who make the world a better place. It’s not a lack of intellectual capacity that progressives should rail against: it’s acts of dishonesty, corruption, cynicism and cruelty—often carried out by highly intelligent and capable people.

We feel that calling people ‘idiots’ isn’t just offensive, it distracts us from the real problems.

Who is prepared to stand alongside us and our lads?

Written with Ramandeep Kaur