Dear Joey,

However we define you, people like you make only the most fleeting appearance in mainstream culture.

There are many reasons, from the traditional disdain for those less articulate ("how could they possibly be interesting?") to the technical challenge of giving voice to those who cannot speak. But it’s a strange history that’s worth exploring, if only because it helps explain modern attitudes.

There is, inevitably perhaps, very little documentary record of the everyday experience of people with your disabilities in medieval and early modern Britain, but they play a surprisingly central role in its art and iconography, especially in the crucial figure of the fool. There were two kinds of fools: the "artificial fools" were witty, intelligent misfits who used the appearance of folly to remind their masters of the truths of life; but the "natural fools" were, for the most part, people with some form of learning disabilities whose role was to remind their masters what it meant to be at the opposite end of the human scale. These "holy innocents", as the traditional Christian called them, were regarded as living embodiments of their saviour’s own simplicity, and the kind of intellectual limitations you display were seen as an expression of humanity’s collective folly. The fool reminded the neuro-typical of his innate imperfections and acted as a "memento mori" as a result. What do you feel about that, I wonder.

The natural fool appears throughout Renaissance culture (there is evidence that some of the great Elizabethan houses employed simpletons—perhaps like you?—as resident entertainers), but usually as a figure of curiosity, as part of a pseudo-scientific exploration of the diversity of human experience, and not as a real-life person in his own right. Even Shakespeare, who’s hailed for including all of human life in his plays, has no character with evident learning disabilities and where he shows people struggling with language and intellectual concepts, it’s because of an underlying lack of education and social privilege, not innate cognitive disability. The depressing fact is, Joey, I don’t think even Shakespeare (who I love and admire) would have seen you as worthy of poetry or drama.

Indeed, reading English literature, one could conclude that people like you didn’t really exist before the late eighteenth century. Wordsworth’s long poem The Idiot Boy (1798) marks a critical turning point. It’s a remarkably affectionate portrait of a young man, Johnny, who, like you, has no speech and evident learning disabilities, but an intimate relationship with the natural world. It caused an uproar in some circles and John Wilson, a precocious seventeen year old fan, was confused by the poet’s choice of subject: "It appears almost unnatural that a person in a state of complete idiotism should excite the warmest feelings of attachment in the breast even of his mother". In a fascinating response Wordsworth offered one of the first written expressions of genuine affection and empathy for people like you:

"But you will be inclined to ask […] how all this applies to The Idiot Boy. To this I can only say, that the loathing and disgust which many people have at the sight of an idiot is a feeling which, though having some foundation in human nature, is not necessarily attached to it in any virtuous degree, but is owing in a great measure to a false delicacy, and, if I may say it without rudeness, a certain want of comprehensiveness of thinking and feeling.

I have often applied to idiots, in my own mind, that sublime expression of Scripture that their life is hidden with God. They are worshipped, probably from a feeling of this sort, in several parts of the East. Among the Alps, where they are numerous, they are considered, I believe, as a blessing to the family to which they belong. I have, indeed, often looked upon the conduct of fathers and mothers of the lower classes of society towards idiots as the great triumph of the human heart. It is there that we see the strength, disinterestedness, and grandeur of love; nor have I ever been able to contemplate an object that calls out so many excellent and virtuous sentiments without finding it hallowed thereby, and having something in me which bears down before it, like a deluge, every feeble sensation of disgust and aversion.

I must content myself simply with observing, that it is probable that the principal cause of your dislike to this particular poem lies in the word Idiot. If there had been any such word in our language, to which we had attached passion, as lack-wit, half-wit, witless, &c, I should have certainly employed it in preference; but there is no such word. My Idiot is not one of those who cannot articulate, and such as are usually disgusting in their persons. The Boy whom I had in my mind was by no means disgusting in his appearance, quite the contrary; and I have known several with imperfect faculties, who are handsome in their persons and features.

This poem has, I know, frequently produced the same effect as it did upon you and your friends; but there are many also to whom it affords exquisite delight, and who, indeed, prefer it to any other of my poems. This proves that the feelings there delineated are such as men may sympathize with. This is enough for my purpose. It is not enough for me as a poet to delineate merely such feelings as all men do sympathise with; but it is also highly desirable to add to these others such as all men may sympathise with, and such as there is reason to believe they would be better and more moral beings if they did sympathise with."

It’s an astonishing letter, which—if one can get past the preoccupation with the boy not being ugly (a disparaging reference to Down Syndrome no doubt) and the use of the word idiot—prefigures many of the most enlightened modern attitudes to intellectual disability. Of course, Wordsworth’s Johnny also acts as a surrogate of the romantic poet, alive to the natural world, unvarnished in his manners and with his roots in the everyday—and granted almost magical powers as a result; but the poem is also a plea for the recognition and acceptance of the existence of people like you, Joey, and is, as far as I can tell, the first time a poet addressed your kind of experience in such a frank and open hearted manner.

Another great writer knew about learning disabilities, but never publically acknowledged it. Like you, Jane Austen’s second eldest brother George was of very limited intellectual abilities and suffered from epilepsy. Her biographer writes that he "was not a Down’s Syndrome child, or he would not have lived so long, lacking modern medication", and adds that "because Jane knew deaf and dumb sign language […] it is thought he may have lacked language." Their father consoled himself with the view that George ‘cannot be a bad or wicked child’ as a result, and there is some debate about how the rest of the family treated George, but no comment by Jane herself survives. Critics sometimes claim that he was the inspiration for "poor Richard" Musgrave, a minor character in Persuasion (1816), but he seems to have had little impact on his sister’s novels otherwise.

Dickens, by contrast, included many characters a bit like you: Joe the Crossing Sweeper in Bleak House (1853), Maggy in Little Dorrit (1857) and, above all, the title character in Barnaby Rudge (1841). If such figures often act as embodiments of Dickens’ broader arguments about the innate goodness of the innocent, we should remember his active involvement in the foundation of Great Ormond Street Hospital (where you’ve been seen, dozens of times), and his article on ‘Idiots’ in Household Words:

"Until within a few years, it was generally assumed, even by those who were not given to hasty assumptions, that because an idiot was either wholly or in part, deficient in certain senses and instincts necessary, in combination with others, to the due performances of the ordinary functions of life—and because those senses and instincts could not be supplied—therefore nothing could be done for him, and he must always remain an object of pitiable isolation. But a closer study of the subject has now demonstrated that the cultivation of such senses and instincts of the idiot is seen to possess will, besides frequently developing others that are latent in him but obscured, so brighten those glimmering lights, as immensely to improve his condition, both with reference to himself and to society. Consequently there is no greater justification for abandoning him, in his degree, than for abandoning any other human creature."

Dickens, as so often, was ahead of his time, but it was in his journalism, not his fiction, that he addressed the issue of people like you most directly. This is perhaps not surprising: writers have often found it difficult to describe such challenging subjects in fiction.

Nineteenth-century Russian and European literature has a handful of characters with learning disabilities. Thus, the central figure of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot (1869) is the simple and trusting Prince Myshkin who, like you, is also epileptic (and is described as a "positively beautiful man"), but his disabilities are relatively mild, and his character is used to explore the impact of such naïve goodness on a corrupt and cruel world. Two more modern—perhaps more three-dimensional—examples are the simple-minded Félicité in Flaubert’s short story Un Coeur Simple (1877) and the innocent Stevie in Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent (1907).

But it’s only in the twentieth century that Wordsworth’s and Dickens’ implied challenge has been really taken up. But here, Cassandra-like, characters with learning disabilities bear witness to the catastrophe of the world around them. Probably the two most famous are Benjo Compson, the central character in William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury (1929), and the simple-minded Lennie in John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men (1937). I prefer Elsa Morante’s innocent young Useppe (in History, 1974), a boy born of rape, whose mother is determined to keep him safe through the catastrophe of the Second World War:

"A merrier baby than he had never been seen. Everything he glimpsed around him roused him to interest and stirred him to joy. He looked with delight at the threads of rain outside the window as if they were confetti and multi-coloured streamers. And if, as happens, the sunlight reached the ceiling indirectly and cast the shadows of the street’s morning bustle, he would stare at it fascinated, refusing to abandon it, as if he were watching an extraordinary display of Chinese acrobats, given especially for him. You would have said, to tell the truth, from his laughter, from the constant brightening of his little face, that he didn’t see things only in their usual aspects, but as multiple images of other things, varying to infinity."

This has an extraordinary vividness, and I can’t read it without thinking of you, my Joey.

In a similar vein, three twentieth-century plays of the German Miserere feature characters with learning disabilities: Swiss Cheese, the second son in Brecht’s Mother Courage and her Children (1939), ends up losing his life because he’s so "simple and honest"; the title role in Peter Handke’s Kaspar (1967) is a young man who’s been brought up in complete isolation and, as a result, has never developed speech; and Frankieboy is an almost entirely silent teenager in Manfred Karge‘s The Conquest of the South Pole (1985) whose presence forcefully demonstrates that even among the long-term unemployed people like you are at the bottom of the heap. But, for the most part, these figures exist as metaphors for powerlessness and exclusion and aren’t fully rounded characters in their own right.

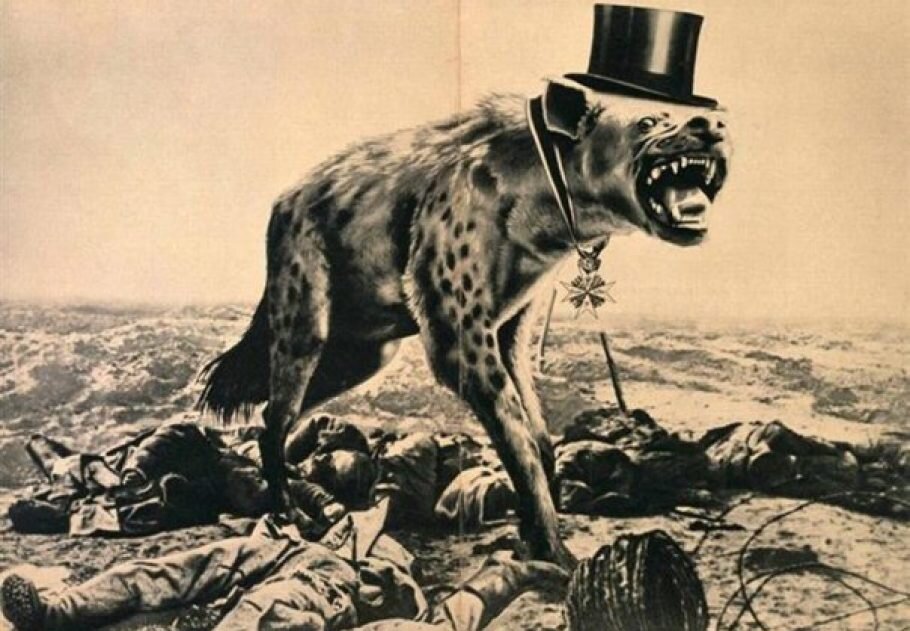

A rare exception is Les Murray’s great poem, Dog Fox Field about the Nazi murder of the disabled. He prefaces it with a note quoting the Nuremberg trials to the effect that "the test for feeblemindedness was they had to make up a sentence using the words dog, fox and field", and it goes to the very heart of that terrible crime:

"These were no leaders, but they were first

into the dark on Dog Fox Field:

Anna who rocked her head, and Paul

who grew big and yet giggled small,

Irma who looked Chinese, and Hans

who knew his world as a fox knows a field.

Hunted with needles, exposed, unfed,

this time in their thousands they bore sad cuts

for having gazed, and shuffled, and failed

to field the lore of prey and hound

they then had to thump and cry in the vans

that ran while stopped in Dog Fox Field.

Our sentries, whose holocaust does not end,

they show us when we cross into Dog Fox Field."

It’s a masterpiece, which manages to be both subjective and objective about the experience of the many "feeble-minded" murdered by the Nazis. But I can’t read it without realizing that it’s a test that you would have failed miserably.

*

I’ve sometimes wondered what pre-scientific people would have made of your epileptic seizures.

It’s hardly surprising that in so many cultures epilepsy carried paranormal connotations. The Ancient Greeks called it "the Sacred Disease" because they saw it, either, as a symptom of devil possession, or as a God-given gift, and such dualism is fundamental to how it’s been perceived in Western societies ever since.

Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine, is a remarkable exception and was spot on when he argued that epilepsy would only lose its mysterious associations when its causes were properly understood:

"Men being in want of the means of life invent many and various things, and devise many contrivances for all other things, and for this disease, in every phase of the disease, assigning the cause to a god."

He describes a range of epileptic symptoms and mocks the way that they are commonly interpreted: "All of these things, they say, are attacks by Hecate and assaults by the Heroes; they make use of expiations and enchantments, and in my opinion, at least, they create a divine power that is most wicked and impious." And, indeed, epileptics have been frequently shunned, presumed to be mad, bad or mentally defective (supported, perhaps, by the prevalence of epilepsy in those with learning disabilities), and I’m afraid your condition still strikes fear into many.

Christianity, for all its exhortations to care for the sick and lame, has tended to offer little more than prejudice when it comes to epilepsy. Thus, one of the core benefits of the baptismal rites was thought to be protection from the "falling sickness", and St Luke tells us that Christ performed a miracle on a young man with epilepsy by driving out "the spirit" that possessed him:

"And, behold, a man of the company cried out, saying, Master, I beseech thee, look upon my son: for he is mine only child. And, lo, a spirit taketh him, and he suddenly crieth out; and it teareth him that he foameth again, and bruising him hardly departeth from him. And I besought thy disciples to cast him out; and they could not. And Jesus answering said, O faithless and perverse generation, how long shall I be with you, and suffer you? Bring thy son hither. And as he was yet a coming, the devil threw him down, and tare him. And Jesus rebuked the unclean spirit, and healed the child, and delivered him again to his father."

Of course, this episode is intended to say more about faith than science, but it’s taken for granted that the young man’s epilepsy is the result of a "foul spirit" within.

Epilepsy has been underrepresented in art and literature and, when featured, has tended to be regarded metaphorically. Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, we’re told, suffers from the "falling sickness" This isn’t an original invention (it’s in the source) and the playwright is evidently fascinated by it (although he doesn’t dramatise any seizures). Once again, though, the condition is interpreted as either devil possession or divine inspiration (the "stigma of the strange" is metamorphosed into the "stigmata of the sacred", one might say), and there’s a fascinating discussion in the play about how Caesar uses his epilepsy to reinforce his popular appeal. Similarly, the proud general Othello falls to the ground with an epileptic seizure when confronted with apparent proof of his wife’s infidelity. Both plays ask the same question: should we trust a leader whose body is so dedicated to his cause that he foams at the mouth and collapses? It’s almost as if the existence of epilepsy is a symbol of the fatal flaw which makes both men’s deaths necessary—but, as usual, it’s not recognised as a neurological phenomenon in its own right.

Victorian writers struggled with epilepsy too. The title character in George Eliot’s Silas Marner (1861) suffers from catalepsy:

"Since the oncoming of twilight he had opened his door again and again, though only to shut it immediately at seeing all distance veiled by the falling snow. But the last time he opened it the snow had ceased... He went in again, and put his right hand on the latch of the door to close it—but he did not close it: he was arrested, as he had been already since his loss, by the invisible wand of catalepsy, and stood like a graven image, with wide but sightless eyes, holding open his door, powerless to resist either the good or evil that might enter there."

These seizures make it impossible for Silas to take his place in conventional, masculine society. Impressively, Eliot charts a shift in the way that his condition is regarded—first as a manifestation of the divine, then as a symptom of Satanic possession and, finally, as a medical issue which deserves broader empathy and care—but throughout we can feel the author struggling with the weight of the traditional interpretations.

It’s thought that Dickens himself suffered from childhood epilepsy, and seizures are evident in three of his characters: Monks, the hero’s villainous half-brother in Oliver Twist (1838), Charley Hexam’s headmaster in Our Mutual Friend (1864-5) and Guster, a maidservant in Bleak House (1852-3), who is—unscientifically—granted control over her ‘fits’, which come about as a result of social pressure. More accurately, she has real anxiety that she’ll lose her job if her condition is discovered. Thus Dickens moves beyond the traditional explanations of epilepsy as "possession", but interprets it according to the social, not the medical, model.

There are, inevitably, more realistic accounts in modern literature. At one point in Peter Nichols’ brilliant black comedy A Day in the Death of Joe Egg (1967), Bri, the father of a child with profound cerebral palsy, acts out an eccentric Viennese neurologist explaining in ‘layman’s terms’ the nature of a seizure. He asks the child’s mother, Sheila, to imagine that the brain is like someone working at a telephone switchboard:

"But at zat moment anozzer incoming call—brr—brr—and you panic and plug him in to the first von and leave zem talking to each ozzer and you answer an extension and he vont the railway station but you put him on to ze cricket results and zey all start buzzing and flashing—and it’s all too much, you flip your lid and pull out all the lines, Kaputt! Now zere’s your epileptic fit. Your Grand or petit Mal according to ze stress, ze number of calls."

All sorts of similarly simplistic stories are told to help people understand something that can be mystifying to the non-scientific mind, and Nichols’ satire brilliantly exposes a new kind of divination. There are, no doubt, othermore scientific accounts of epilepsy in contemporary fiction and drama.

Today there’s a huge amount of useful information available from various organisations that explains epilepsy in reassuring scientific language and I can’t pretend that you’ve been subjected to much discrimination or stigma as a result of yours. And so I find it difficult to explain exactly why your condition disturbs me so much. The epilepsy campaigners would criticise me for further mystifying what is a well-understood medical issue, and I respect their position. It doesn’t, however, resolve the pain I feel in seeing someone I love in a state of abject helplessness, consumed by a physical phenomenon over which he has no control, and which I can do so little to help.

When working on Joe Egg, I was forcefully struck—probably as a lapsed Catholic—by an apt metaphor for what I was experiencing. Seeing the character of Bri carrying his poor daughter (also a Joe) in his arms in mid-seizure suddenly reminded me of a Renaissance painting of the Deposition of Christ: it’s an image of a human body in a state of total vulnerability, held and protected by the people who love and worship him, who are in an agony of concern for his suffering, of which he can have very little knowledge, but about which they can do almost nothing. And when you’re lying across me after the seizures have passed I sometimes feel an insight into the Pietà itself: the body of the dead Christ lying across his grieving mother’s lap.

And then, of course, you come round, dust yourself down and get on with something more interesting, leaving me grasping pointlessly for metaphors and meaning.

*

In the past, I’m afraid, people like you have sometimes been regarded as legitimate objects for scorn, and bullied, abused and persecuted as a result. Most of the time, they’ve been dependent on the care of their families and charities of one kind or another but, where this has failed, they’ve been at the mercy of an uncomprehending world, often to disastrous effect. In Britain, until the late 1960s, most families were persuaded to place their learning disabled child in a medical institution. Indeed in many societies people like you have been murdered or simply abandoned as too challenging, too distressing or too expensive. And it still happens in some places. Although the lives of most learning disabled people in Britain are better than they’ve ever been, we shouldn’t forget the history of persecution, nor the belief systems that made it possible. Advances are all too easily reversed and we should never forget, as Edmund Burke warned us, that "all that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing."

Christianity, it seems, has come up with two contradictory ways of talking about parenting a child like you. The first is that you’re God’s punishment for past misdeeds. Thus, an American politician, Bob Marshall, Republican Member of the Virginia House of Delegates, has repeatedly claimed that disabled children are God’s punishment to women who had aborted their first pregnancy. And the devoutly religious, but deeply confused, Glenn Hoddle, the one-time manager of the England football team, was sacked when he declared: "You and I have been given two hands and two legs and half decent brains. Some people have not been born like that for a reason; the karma is working from another lifetime. I have nothing to hide about that. It is not only people with disabilities. What you sow, you have to reap." And there are historic accounts of terrible cruelty and abuse towards people with learning disabilities in various Catholic care homes and institutions in Ireland and elsewhere.

Fundamentalist Christianity doesn’t have a monopoly on such pernicious nonsense, however. The explicitly secular Nazis labelled those with profound disabilities as living "lives unworthy of life", or "useless eaters", and the persecution, forced sterilization and subsequent murder of perhaps a quarter of a million disabled people under the T-4 programme paved the way for the even greater genocide of the European Jews. More recently, one of the most extreme animal rights philosophers, Peter Singer, a Professor of Bioethics at Princeton University, argued that human beings like you who fail to develop the ability to speak are in some ways less than human, on a par with animals. In Practical Ethics he insisted that "killing a disabled infant is not morally equivalent to killing a person. Very often it is not wrong at all", basing his argument on the relative capacities of animals: "If we compare a severely defective human infant with a nonhuman animal, a dog or a pig, for example, we will often find the nonhuman to have superior capacities, both actual and potential, for rationality, self consciousness, communication and everything else that can plausibly be considered morally significant." Thankfully, Professor Singer is not in power.

Closer to home, the Independent councillor, Colin Brewer, argued that "disabled children cost the council too much money and should be put down", while a UKIP member, Geoffrey Clark, called for compulsory abortions of disabled foetuses. And a Tory deputy mayor, amazingly enough a retired GP called Owen Lister, argued that disabled children like you should be "guillotined", explaining that "the only difference between a terminally ill patient and a severely handicapped child is time."

Perhaps most shocking of all—because it’s so surprising from a card-carrying liberal—is Virginia Woolf’s diary entry for 9th January 1915—where she writes that:

"On the towpath we met & had to pass a long line of imbeciles. The first was a very tall man, just queer enough to look at twice, but no more; the second shuffled, & looked aside; and then one realised that every one in that long line was a miserable ineffective shuffling idiotic creature with no forehead, or no chin, & an imbecile grin, or a wild suspicious stare. It was perfectly horrible. They should certainly be killed."

Woolf, of course, was simply mirroring the common views of the Eugenics Society, whose Chairman, the distinguished biologist Julian Huxley, wrote in 1930:

"What are we going to do? Every defective man, woman and child is a burden. Every defective is an extra body for the nation to feed and clothe, but produces little or nothing in return."

Many public figures, including birth control pioneers Margaret Sanger and Marie Stopes, politicians Winston Churchill and Theodore Roosevelt, and proud liberals such as H. G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, John Maynard Keynes and Sidney Webb all supported eugenics. Thankfully, it’s now been dismissed as pseudo-science of the worst kind that, in Britain at least, does little but discredit the speaker. More recently, the eminent geneticist and proselytising atheist Richard Dawkins, in response to an enquiry from a woman about what to do if she discovered that she was pregnant with a foetus with Down Syndrome, replied "abort it and try again. It would be immoral to bring it into the world if you have the choice." He denied that he is a eugenicist, but it’s hard to understand what he means by the word "immoral" in such a context.

Lower level discrimination exists too. Research by the leading health and social care provider, Turning Point, showed that a bias against those with learning disabilities is widespread in modern Britain. The Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities concluded that "people are more comfortable interacting with people with physical or sensory impairments in social situations than they are […] with individuals with learning disabilities or mental health conditions". The consultancy Lemos&Crane produced a devastating report entitled Loneliness+Cruelty about the bullying of people like you, and the Papworth Trust has published research showing that 90% of people with learning difficulties have experienced hate crime or bullying, with almost a third saying that it takes place on a daily or weekly basis. And, finally, UNICEF concluded in 2012 that "Disability is not the impairment itself, but rather attitudes and environmental barriers that result in disability". Children with disabilities are often "invisible’ to service providers, and they are at greater risk of violence than their non-disabled peers." This is all deeply dismaying stuff.

*

Thankfully, you’ve pretty much avoided such discrimination, but your circle has been kept deliberately small, and we’ve worked hard to keep you safe. But as you move into adulthood I’m sure you’ll come across such attitudes more often. It’s a terrifying prospect, but why does it happen? I increasingly think that at the heart of such attitudes—and actions—lies a toxic mixture of fear of that which is different, and the pleasure that some people feel in exercising power over the vulnerable. There’s little that can be done about the second, apart from protecting you from such sadists, but the deeper issue of irrational anxiety can and must be addressed.

I suspect that it’s counter-productive to mock or criticise this fear, and the important first step is to acknowledge the fact of its existence. Its causes are invariably complex and as much a result of self-consciousness ("How will I be able to cope?", "Will I hurt the disabled person?", "What if the disabled person wants me to do something I’m not comfortable with?") as terror of the alien or the strange. As with all phobias, people can be exposed gently to the object of their fear, and learn to recognise that there is no basis for it. It’s the essential first step.

And so I was thrilled to see a film about a theatre group committed to raising disability awareness among young people. They go into schools and ask able-bodied children to enact the challenges their disabled peers face: crossing a room without using their legs, eating dinner without using their fingers, or communicating their wishes without using any words. I’m convinced that educational work like this—the normalisation of learning disability, you could call it—is essential, and that awareness training should take place in schools and hospitals, offices and factories, social club and hotels. In other words, we need to get to a position where learning disability isn’t seen as an opinion, a prejudice or an emotion, but is acknowledged as a fact of life that could affect anybody. Disability can be challenging for all kinds of reasons, but society needs to be shown that it’s possible to be with disabled people—even people with profound learning disabilities—and that they won’t hurt you.

A huge part of my journey has been to acknowledge and accept your differences, and to do so I’ve had to overcome my own fears and prejudices. But thankfully, as a result, people with learning disabilities hold no fear for me anymore. As your six year old sister memorably said: "you don’t need to be afraid of Joey: he’s just disabled."

On the reverse side of this dismal history of neglect, discrimination and persecution, is a strange story of admiration and wonder, verging at times on adulation. It’s a peculiar phenomenon that can seem patronising at times, but shouldn’t be ignored.

Thus Christianity, when not indulging in the kind of hatred described above, offers a much more creative formula: namely, that the learning disabled child is a special gift from God, who plays an important part in His mysterious plan. Many Christians would argue that you have come into the world to make the rest of us better people, and that you offer new and important insights into the meaning of life. You’re a sancta simplicità, a "holy innocent" who bears witness to the truth of life by witness of your very naivety. Your suffering body—like Christ’s itself—"takes away the sins of the world" and the mysterious nature of your presence makes us all into better human beings. You’re the perpetual child who understands nothing of the corrupted currents of this world, but whose very existence offers hope for all our salvations.

More practically—and perhaps more usefully—the Christian believes that we owe a duty of care to our less able brothers and sisters, including those with learning disabilities like you. Many of the best facilities for disabled people have their roots in religious charity, and I’m continually impressed by the underlying Christian values of care and compassion so obviously on display at Centre where you’re currently resident. What’s more, as Richard Evans so vividly chronicles, it was the courage of a handful of religious leaders, above all the conservative Catholic Bishop von Galen of Münster (1878-1946), whose sermons in 1941 brought about a marked reduction in the Nazi T-4 programme of sterilisation and murder of the disabled: "These are people, our brothers and sisters," he preached, "maybe their life is unproductive, but productivity is not a justification for killing". Although the deadly consequences of the debate have thankfully disappeared, this central question—that of ‘productivity’—is strikingly resonant in a culture which finds it difficult to establish non-monetary value (even reputation and trust can be costed apparently), and which too easily resorts to the language of investment and cost effectiveness when describing education and care for people like you.

An inability to speak—non-verbalism—casts a particular shadow across the debate. Christianity declares that "In the beginning was the word, and the word was with God and the word was God," and man’s ability to speak to God and understand Him is a central aspect to being "created in His own image". And many faiths—not just Christianity—maintain that speech is the outstanding characteristic of our humanity. Thankfully, the creation of other forms of language is taken as evidence of the human ability to communicate the soul, but the particular status of speech is a peculiar lacuna into which those without it can easily fall.

Religion gives many parents of kids like you powerful narratives to explain what is a frequently bewildering experience. And research has shown that the religious (especially, though not exclusively, Christians) handle the situation with greater equanimity than self-confessed atheists like me. As a committed atheist, I can’t accept a divine order in which you’ve been specially designed in order to improve others, but I do recognise—and am sometimes jealous of—the great attraction of such beliefs. More importantly, I have a growing respect for the religious vocation of caring for the weakest and most vulnerable members of society.

*

The secular world offers its own particular brand of consolation.

The 2012 London Paralympics were a mixed blessing for disabled people: on the one hand, they raised the profile of athletes with serious physical disabilities and allowed the general public to see the courage, skill and strength of a group of people they might otherwise have dismissed; on the other, they made it seem that for someone with a disability anything was possible if only you try hard enough. Learning disabilities had an extraordinarily low profile (to be fair, this was the first Paralympic Games that allowed people with such disabilities to compete—nine athletes won medals—and the development of the Special Olympics is redressing the balance further) and I was shocked to hear that Channel 4, the otherwise impressive Paralympics media partner, was still asking disabled people, a few short weeks after the Games, to take part in The Undatables, the freak show about the difficulties supposedly unattractive people face in meeting partners.

As a rule, the British media is drawn to two different stereotypes of disability. On the one hand is outright tragedy, usually culminating in a death; but better are heart-warming stories of triumph against the odds. And so there was a television programme about a boy with cystic fibrosis who went on to conduct an orchestra; a film about a lad with Asperger’s who travelled around America in pursuit of his rock star idol; and a novel—and then a play—in which the high-functioning autist is a mathematical genius. I found the recent Horizon programme Living with Autism (2014) a bit sentimental in its presenter’s emphasis on the high-functioning exceptions, but Louis Theroux’s Extreme Love (2012) seemed much more representative. These, for the most part, make for good infotainment but (as Mark Haddon, the author of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time himself agrees) don’t say much about the realities of profound learning disabilities.

The same issues affect most TV and film dramas on the subject. Thus, the central characters in My Left Foot (1989), Rain Man (1988) and Forrest Gump (1994) all achieve remarkable things despite their disabilities—and have garnered Oscars for the leading actors partly as a result—but say little about the much more common low-functioning disabilities. The uncomfortable fact is that the level of learning disabilities that affects you and your classmates has a shockingly low profile on television and in film and I’m unaware of any character with such disabilities in a soap opera or a mainstream television drama. And I’ve never seen a TV documentary about people with the degree of learning disability that affects you. It’s a shocking omission.

*

Attitudes towards learning disabilities are changing, but much too slowly. Improving cultural representation will certainly help. But what can broader society do? What can we all do? And, finally, what can I do?

There is, sadly, a hierarchy in disability as in so much else, with the high functioning physically disabled at the top and those with profound learning disabilities relegated to a position at the bottom. At its worst, it sometimes feels as if people like you belong in the outer circle of disability Hell, a place that many people find too difficult to contemplate, certainly too painful to enter. This is a place where those most in need often find it impossible to express their wishes, and where the rational discourse of those who want to help finds no echo. It’s also a place where human dignity often seems profoundly compromised, and where the appropriate behaviour of civilised society has been abandoned. Of course, the reality is much more complicated, but a superficial understanding of learning disability often leads to such conclusions. This hierarchy needs to be dismantled urgently, and any discussion about disability needs to take into account those with learning disabilities alongside those with physical ones.

I recognise that we’ve been lucky. But there are so many stories of lamentable standards in the care of people like you, a kind of ghetto mentality which regards all such people as a problem to be borne, as cheaply as possible, and with as little personal investment as possible, that it’s possible to identify a pattern. The appalling stories of abuse and cruelty at Winterbourne View—along with the two terrible incidents of "death by indifference" in institutions run by Southern Health, and other scandals—may be appalling exceptions, but they’re only possible because of a fatal combination of extreme vulnerability of the people in their care and society’s failure to ensure that they are safe. The resulting reaction against ‘institutionalisation’ is laudable but (as we have discovered), care in the community has distinct limits, and a decent society must ensure that people with severe learning disabilities can live safely with dignity, love and happiness in whatever setting. We expect such things for our neuro-typical children as a matter of course, and we should insist on it for their less fortunate brothers and sisters. Everyone—disabled and non-disabled—deserves nothing less.

Politicians, journalists and activists, trying to show their commitment to the disabled, often speak of "realising their potential", of giving "them the opportunity to take their place in society’, or ‘removing the barriers to their progress". This is a good and noble ideal and, certainly, all blocks that stop disabled people doing what they can should be removed, wherever possible and by whatever means. But those with profound learning disabilities pose a kind of challenge that bypasses all such good intentions. The fact is that you will never be productive in the sense that capitalism recognises, celebrates and rewards. Your potential is extraordinarily limited, and it’s impossible for you to do most of the things that these people expect of you. You’re way beyond their reach and they need to accept the fact and recognize the consequences that flow from it. And, in doing so, they might learn that the values on which their social order has been built can and should be questioned.

The human search for meaning invariably turns to narrative. This is the way we make sense of many aspects of our life. And so it’s hardly surprising that people who care about disability are always on the look out for a story. Indeed, at the heart of this book has been the story of how an overeducated and privileged man has tried to come to grips with something far beyond what he thought he could deal with. The problem, however, is that such narratives are, for the most part, irrelevant. There are no narratives to describe you: you exist outside of the world of story, of change, even of meaning. One could argue—as I’ve done—that your existence inspires love in all sorts of people and has brought a large, diverse family together with a new understanding of vulnerability and innate value. But the bitter truth is that the opposite could easily have been the case and you could have been despised, rejected and ignored. I’m proud of what we’ve done, but I’m acutely aware that we are the product of a particular time and place. The truth is that you just are, and the only sanity lies in accepting that existential fact. This is a tough challenge for everyone, but it’s where wisdom is to be found.

In his Apology, Plato quotes Socrates as saying that "the unexamined life is not worth living". This is usually cited as a celebration of the life of the mind and as an exhortation to the intelligent to use their gifts (it was Socrates’ justification for choosing death over exile or enforced silence). But, as the philosopher (and mother of a daughter with profound learning disabilities) Eva Feder Kittaj movingly argues, it’s less useful when used to value those who are incapable of such examining:

"How can one unquestioningly read and teach texts that give Reason pride of place, when each day one interacts with a wonderful human being who displays no indisputable evidence of rational capacity? How can one view language as the very mark of humanity, when this same daughter can speak not a word? How can one argue that our moral worth as ends in ourselves, or as persons, is predicated on the capacity of reason when that would mean that my daughter would not have intrinsic worth?"

As a firm believer in the power of reason, I live with the same set of contradictory emotions. If you’re incapable of complex thought and analysis, why do I continue to value it so highly? There are ways through this conundrum—above all that these powers should be used for the good of all (including, perhaps especially, those incapable of it)—but it’s hard balancing the two.

In summary, then, I think you pose a deep philosophical challenge to the rest of us. There are no consolations, no easy meanings and no all-embracing fictions that will make sense of you. You live in a place far removed from our tidy assumptions about the meaning of life and prove, yet again, that "There are more things in heaven and earth […] than are dreamt of in your philosophy"’. And anybody who denies that—from whatever perspective—is, I’m increasingly sure, simply clutching at straws.

*

The strange thing, I increasingly believe, is that if we respond carefully to the challenges that you and people like you pose, you can have a dramatic impact on the way that we think about our own lives and the world in which we live. And this, I’m convinced, will make for a better world. These challenges make themselves felt in four interrelated areas.

The first is that people with severe learning disabilities like you can help us rethink the priority that we grant to intelligence as the single most desirable of all human qualities. Instead, I believe, we should ask whether clever people are in themselves an absolute good—whether the brightest aren’t always necessarily the best—and ensure that we subject that intelligence to radically different criteria, above all that such intelligence is being deployed to improve the quality of life of all people, regardless of their cognitive abilities. Thus intelligence, you’ve taught me, needs to be useful and not seen simply as an unquestioned good in its own right. And that has challenged me—and many people whom I know and love—in the deepest part of my being. For I recognise now that it was a kind of intelligence that led to the lie of ‘eugenics’ that threatens people like you in the most fundamental way and which, in a less terrible way, justifies the growing gap in the rewards enjoyed by those with intellectual gifts in comparison to those less gifted. And I’ve discovered that ‘stupidity’ isn’t the worst thing that can afflict a person or a family, and that when we hear people being dismissed as idiotic or stupid, we should offer the counter-argument that people with learning disabilities—the real idiots—hardly ever do any harm to anyone: in fact, it’s impossible to imagine you deliberately hurting anyone, or behaving in a way that could possibly cause damage or destruction. And what’s more, such decency and benevolence is much more than can be said of most people with infinitely greater intellectual abilities. The cases of people with profound autism who are destructive and inflict physical pain are rare, and their behaviour is exacerbated by the incomprehension they face from the family and the world at large, and often triggered by particular (and insufficiently understood) factors in their environment. Their outbursts should be managed and pitied rather than feared or despised. And so you have shown me that there are things more important than cleverness, and that we should ensure that our lives and thoughts acknowledge that simple fact.

The second challenge is to our emphasis on productivity as a central element of our evaluation of human worth. Increasingly, young people are brought up to believe that there is nothing more important than what they achieve in life: productivity is all, and the emphasis in education on exams and quantifiable achievements just increases that pressure. It’s a kind of insanity which is leading many to depression and despair. Similarly, in adult life, the first question many of us ask each other is about their work, about what is being made, about what is being produced, about what we’re achieving. Society readily criticises people who don’t want to work—the work shy, the "useless eaters" of Nazi propaganda—and politicians still try to persuade us to resent people who are dependent on benefits and fail to contribute their "fair share", the "shirkers" not the "strivers". Of course, this is a complex moral argument, and I’m not arguing for a life spent watching daytime television, but one of the things that people with severe learning disabilities show us is that there are things more important than such productivity, and that the moment we judge people simply by what they achieve, what they make, what they do, we enter a kind of hell which excludes those who are incapable of such things.

The third challenge that you pose is in the priority we give to written and spoken language in our understanding of the nature of human communication. It’s sometimes argued that spoken language is the key difference between human beings and animals, and that the capacity for speech lies at the heart of our definition of what it is to be human. But at the age of 21 you have no words at all and pitifully limited abilities to communicate through writing, and yet you manage to express your wishes, fears and desires in so many other ways; eyes, hands, smiles, gestures, fingers and posture. So long as we assume that communication simply means the use of spoken or written language, we will fail to understand not just those who are non-verbal, but the myriad of other means that neuro-typical human beings use to communicate with each other.

The final way that you challenge our thinking is in the indefinable area of human happiness. People often ask me whether you are happy and, while it’s difficult to know for certain, my instinct is that you’re happy most of the time, certainly happier than I am or the rest of your immediate family, or most of the neuro-typical people that I know and love. It’s easy to patronise you for your ability to be made happy by the simplest of things, but it’s perhaps wiser to be jealous of this capacity. And in a time when psychiatrists detect a new kind of depression stoked by a superfluity of material goods ("affluenza", as Oliver James called it), your deep and profound pleasure in willow trees, in bunting, in flowing water, and in the oldest of old jokes should perhaps make us pause before we imagine that an iPad, a holiday, new clothes or an expensive restaurant will bring us much in the way of real joy and contentment.

For all its horrors, the twentieth century successfully expanded our understanding of what it is to be human, and a growing awareness of diversity challenged mainstream views in the most fundamental ways. Socialism helped provide a view of society from below, just as feminism made people aware that male experience was not the only perspective available. And the great struggles against racism, homophobia and religious persecution allowed us to learn more about people who may be different in fundamental ways, but who are as capable of the same feelings as we are and as deserving of the same respect. The campaign for the rights of the disabled has been a relatively recent phenomenon (as is evident in the discrimination expressed by people of otherwise impeccable liberal credentials), but it has made significant inroads, especially in the area of physical disability. But it is in the deeply unfashionable and profoundly challenging area of severe learning disabilities that the greatest fight for acceptance lies. And it’s here, I believe, that society now needs to direct its gaze and fight for improvements in the lives of people like you, and so broaden still further our understanding of what it means to be human. It’ll make for a better society for everybody.

*

We live in a world of endless noise and chatter. We’re all encouraged to develop carefully manicured views and self-expression is regarded as a fundamental human right. But who will speak for those who cannot speak? Who is prepared to provide a voice for the voiceless?

And it’s this, above all, which has prompted me to write this little book: the knowledge that there is a whole swathe of human experience—silent, limited and, to a large extent, hidden—which our society almost always ignores. Andrew Solomon’s account of Cris Donovan, the mother of a profoundly disabled child, struck a deep chord in me:

"Towards the end of the weekend I spent with the Donovans, Cris mentioned that she was feeling good about her New Year’s resolutions. I asked her what they were. ‘You are part it, actually,’ she said. ‘I resolved to do things that I’m afraid of. Doing this—talking all about myself and the hardest parts of my life with you—is something I can give back to the world and I decided just to do it, and I’m glad I did. It helped me to lay it all out like this; it helped me see how hard it all is, and how terribly much I love our son"

Like Cris, I’ve found meaning in telling as many people as possible about you and making them aware of the issues that you face. And so I understand all too well Rachel Adams’ experience of writing about her disabled daughter:

"Writing became a way to claim those experiences as my own, to resist the sense that I was living out a story someone else had already written. But it was also about accepting our participation in a broader collective experience. The more I wrote, the more I realised I was speaking not just about Henry and me, but about a whole class of people who, for much of human history, had been hidden from view."

Writing and talking about you and what you’ve taught me is one of the few things that I feel I can do to help.

When I wrote in The Guardian that "being clever isn’t everything", some people misunderstood me, as if I was arguing that sloppy thinking was ok. This, of course, couldn’t be further from the truth: I value literacy, language and intellectual discrimination as much as ever, in some ways more. But what the experience of you has reminded me, again and again, is that there is no hierarchy in human beings; that all people, whatever their abilities, are born equal and must be treated equally; and that when decisions are made about how we should organise our society and try to make a better world for everyone, nothing is too good for those who cannot help themselves.

And I’ll always be grateful to you for showing me that.

Dad

So terrible being the dad of a learning disabled young man. pic.twitter.com/innKcdKFje

— Stephen Unwin (@RoseUnwin) January 1, 2021 " target="_blank" class="sqs-svg-icon--wrapper twitter-unauth">