So today the country I call home gives up its membership of the European Union. There are so many reasons to regret this preposterously self-destructive act of vanity, that it’s hard to know where to start.

The most substantial issue is, of course, the economy. The plan to break away from the biggest and most successful single market in the world, only 21 miles away, in order to trade with and offer services to - what?- Sri Lanka and New Zealand is self-evidently absurd. The Brexiters huff and puff about Project Fear, but things will change when the economy suffers, especially if no deal is negotiated and we end up trying to trade ‘on WTO terms.’ The country may have spent four years indulging in identity politics but it’s still ‘the economy, stupid’ that ultimately matters.

But what I want to address here is the tone of the debate and its consequences. And to do that we need to go back to the immediate aftermath of the referendum. Responsible politicians would have stated the obvious: that the outcome was close, informed opinion was worried, and that the best option was a cross-party agreement which tried to deliver on the result but with minimal economic fallout. They would have emphasised the rule of law and the supremacy of parliament and reminded everyone that the referendum was ‘advisory’. Above all, they wouldn’t have triggered Article 50 until they’d secured broad support. Brexit is far too serious a matter to be left to one bitterly divided political party. Instead, Theresa May, terrified of her ultras, repeated the meaningless phrase ‘Brexit means Brexit’ and the endlessly prevaricating Jeremy Corbyn was no better. Terrible political leadership simply weaponised the already toxic debate and what should have been a question of grave national concern was politicised in the worst way possible.

So many things have been coarsened by this whole sorry mess, and it’s difficult to know how we’ll emerge. But, it seems, some fundamental British values are under threat. Look, for example at the attacks on knowledge and expertise. ‘The British people have had enough of experts’, declared Michael Gove, and soon all opinions, however ignorant, were regarded as equally valid. But this isn’t how we operate in the rest of life and certainly shouldn’t apply to the extraordinary complexity of international trade and cross border services, let alone the intricacies of the Northern Ireland peace process or the transport of time sensitive medicines. ‘Facts are stubborn things,’ said John Adams, and all too often in this row, the facts have been twisted and falsified, not just by the newly empowered Twitter mob (on both sides), but the Brexit leadership itself.

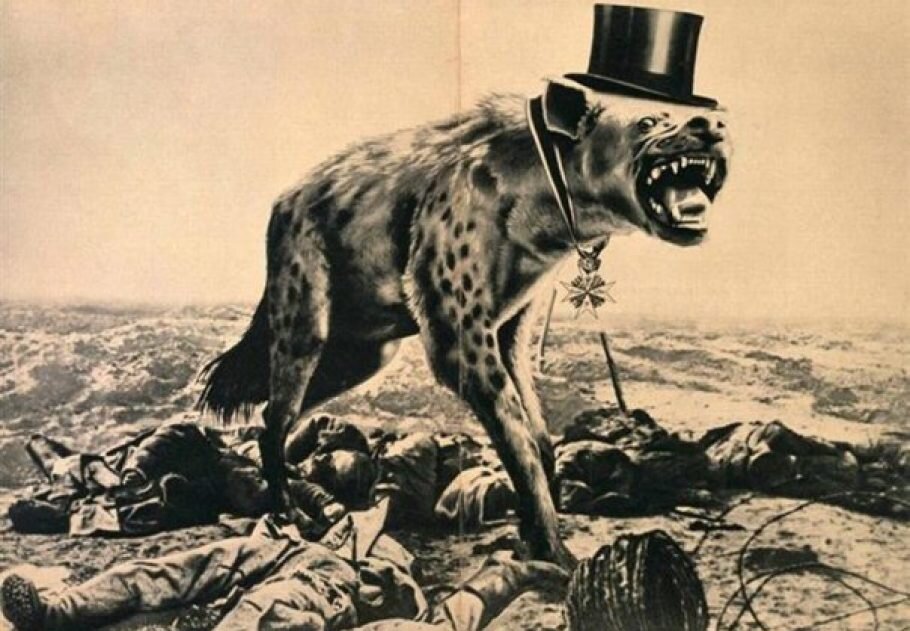

One of the most shocking developments has been the demonising of the ‘elite,’ a group apparently dedicated to opposing ‘the will of the people.’ This kind of language has a terrible pedigree: Goebbels used the ‘people’s community’ to justify Nazi atrocities, Stalin’s dictatorship was predicated on the persecution of anyone who wasn’t a worker or a peasant, and Mao and Pol Pot killed millions of people who just wanted to get on in life. ‘Dear’, my great teacher, Margot Heinemann said, ‘be careful not to use the phrase “the people” in the way Hitler would have done,’ and all dictatorships turn their backs on experts, with fatal consequences to millions, including, of course, the ‘people’ whose interests they claim to be championing.

This kind of language is built on deep felt resentment and an inferiority complex. Indeed, it’s notable that the Brexit leaders have consistently ignored the real divide in this country, between the rich and the poor, partly because so many of them are millionaires themselves. (It’s a funny world when the supposed tribunes of the people are millionaire Etonians). Instead, they’ve attacked the 48% (52% now) who supported Remain as ‘out of touch metropolitans’ who want to ‘overturn democracy’. It’s as absurd as it’s dangerous, but who are these sixteen million people who ‘ordinary people’ are being encouraged to despise? They include school teachers and academics, police officers and lawyers, economists and accountants, consultants and businessmen, doctors, nurses and scientists, as well as writers, entertainers, trading experts, sportsmen and women, unionists, musicians, intellectuals, engineers, civil servants, judges and on and on: in fact, a whole range of people that a civilised society needs onside if it’s going to function. ‘Hang all the lawyers’ proclaims one of Jack Cade’s followers in Henry VI, and for the Brexiters to attack this huge group of professionals and encourage a mockery of their knowledge, commitment and expertise, is deeply counterproductive. Brexit Britain will need the goodwill and commitment of these people if it is to survive the icy cold sea we’ve been thrown into.

When challenged about the nature of their fantasies, Brexiters offer a range of answers, including questionable notions of a democratic deficit, the cost of membership, and the issues raised by European immigration. And when confronted by the many concerns expressed by all sectors of informed opinion, they tell us that their project is about something other than prosperity, it’s an emotional sense of belonging which we, as ‘people of nowhere’ couldn’t possibly understand. They’ve been ignored for far too long, they moan, and it’s time that their dreams of independent nationhood were realized. Apart from the fact that Britain’s independence was never actually threatened by British membership, and many of us ‘elitists’ have problems of our own to deal with, we should, perhaps, counter this ludicrous attempt at monopolising patriotic emotion by sharing our own feelings about Britain and its place in the great continent of Europe. The Brexiters will say that we’re only leaving the bureaucracy of the EU, not Europe itself. In which case I look forward to a leading Brexiter proclaiming his identity as a European, instead of dreaming of another time when, it’s thought, Britannia ruled the waves. It’s long past the time for us proud Europeans to shrug off the Union Jack and stand up for what we care about, and, at last, talk about what we feel. Brexiters shouldn’t be allowed a monopoly in emotion.

The truth is, I am first and foremost a European. My mother was born in Germany, my father’s family comes from Ireland. My main language is English, but I can also manage in French, German and Italian. My cooking is mostly poor imitations of French and Italian and I drink European wine and beer. I take most of my holidays in continental Europe and many of my formative experiences were European. My great teacher was the daughter of Jewish refugees and many of my favourite novels, plays and works of art are European. The vast proportion of the books in my library are European (yes, I include English literature in that category) and hundreds are translations from European languages. European blood runs in my veins and I’m acutely aware of the enduring impact of Greek and Latin on all aspects of the civilisation in which I live.

What’s more, while I have a penchant for late twentieth century American music and love Chinese food, my attitude to the individual and society are distinctly European. In the USA I find myself in a very strange land which champions the individual above any sense of shared social responsibility and so often resorts to sentimentality as a way of dealing with difficulty. When I go to China, the opposite end of the spectrum, I’m shocked by the sense of the massive scale of the country and an underlying brutality in the way it regards the individual. I dread to imagine how my profoundly disabled son, Joey, would have managed to thrive in either country. Postwar Europe offers a kinder, better way of being human, and we leave that family of beliefs at our peril.

And so when I look out across the Channel I know that my heart belongs to Europe and it always will: its culture, its history and its way of life. What’s more, I know that the country in which I live, the country that I will always love despite this dreadful mistake, has played a hugely important and creative part in the making of the uniquely European civilisation. Our pragmatism, our tolerance, our professionalism, our inventiveness, our creativity, our skills and our talents, our passion and our commitment. And we in turn, ever since the Norman Conquest, have benefitted hugely from the Continent, in so many ways. Just think, for a moment, of the huge benefits of the various waves of Jewish immigration, especially, of course, in the 1930s. The great European movement that emerged after the war was a way of putting nationalist division aside, not eradicating national character, and it’s part of the Brexiter strategy of resentment and self-pity to fail to see the astonishing mutual benefit of our membership. And so in response to reactionary nostalgia, I suggest we should reassert the astonishing achievements of Britain’s essential role in European civilisation, from the abolition of slavery to the promotion of women’s rights, from William Shakespeare to Stephen Hawkins, the best of us, working together, have made all of Europe a better, happier place. The tragedy is that a small group of resentful reactionaries have dragged us away from that extraordinary achievement. We can only hope that their nationalism doesn’t lead us back into the disasters of the Europe of only a hundred years ago.

Our job now—as ‘elitists’, ‘remoaners’, ‘traitors’, and ‘enemies of the people’—is to hold the Brexiters’ feet to the fire. For years they’ve posed as the insurgents, they’ve moaned and complained and mocked and whined, they’ve dubbed themselves ‘bad boys’ and made clear that nothing is ever good enough for them and showed that their self-pity knows no ends. Well, they should have been careful what they wished for, because whatever happens now they’re responsible for it, from the Prime Minister right on down to the good voters of Sunderland. Of course, they’ll try to blame everyone else: the EU, the Remainers, and, no doubt, immigrants and the disabled and anyone else who doesn’t fit into their view of what British people should be. But we must call them out on that, every step of the way. There was something good and they broke it. And now they must be made to own it. It’s the Brexiters and the Brexiters alone who are to blame for what happens next.

The whole world is watching, their mouths wide open.

So terrible being the dad of a learning disabled young man. pic.twitter.com/innKcdKFje

— Stephen Unwin (@RoseUnwin) January 1, 2021 " target="_blank" class="sqs-svg-icon--wrapper twitter-unauth">